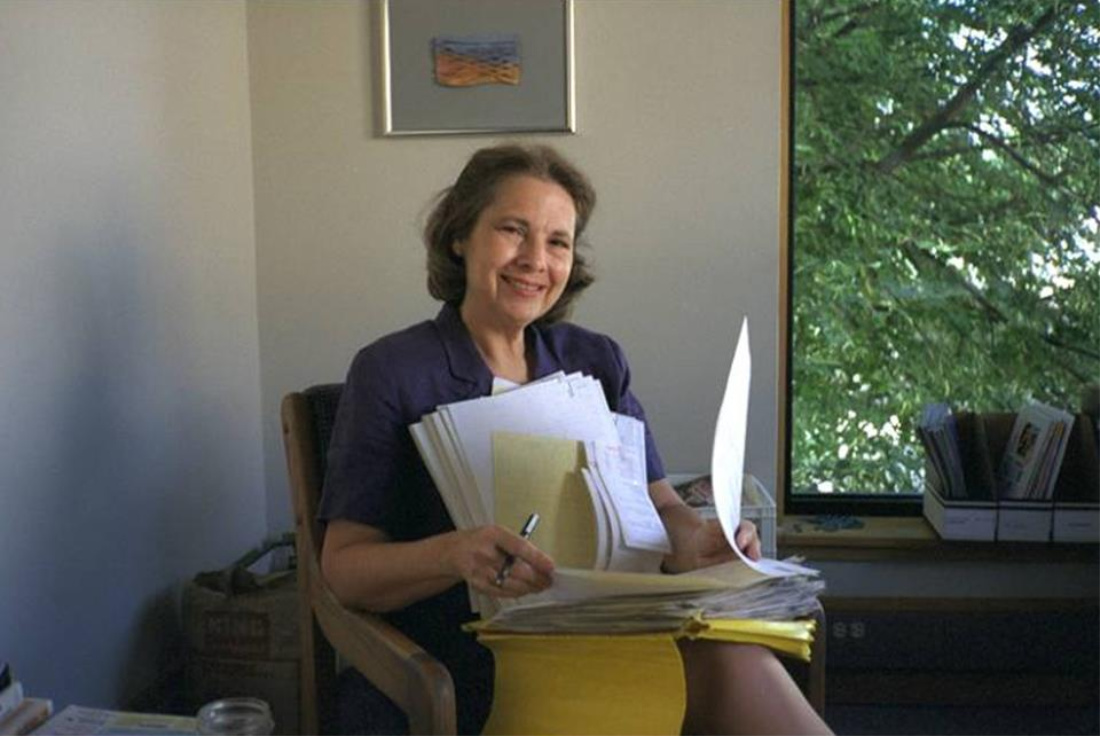

Linda Ligon going through a stack of papers in the Interweave offices sometime in the mid-1990s.

Now, Interweave is facing a very uncertain future. Its parent company, F+W, filed for bankruptcy in March and the search is on to find a buyer for the books division and the magazines by June. Before that happens, I thought we as a community could take a collective breath and look at the tremendous impact that Interweave has had over the last 44 years. This company has touched so many of our lives in meaningful, career-changing ways.

No End to Growth

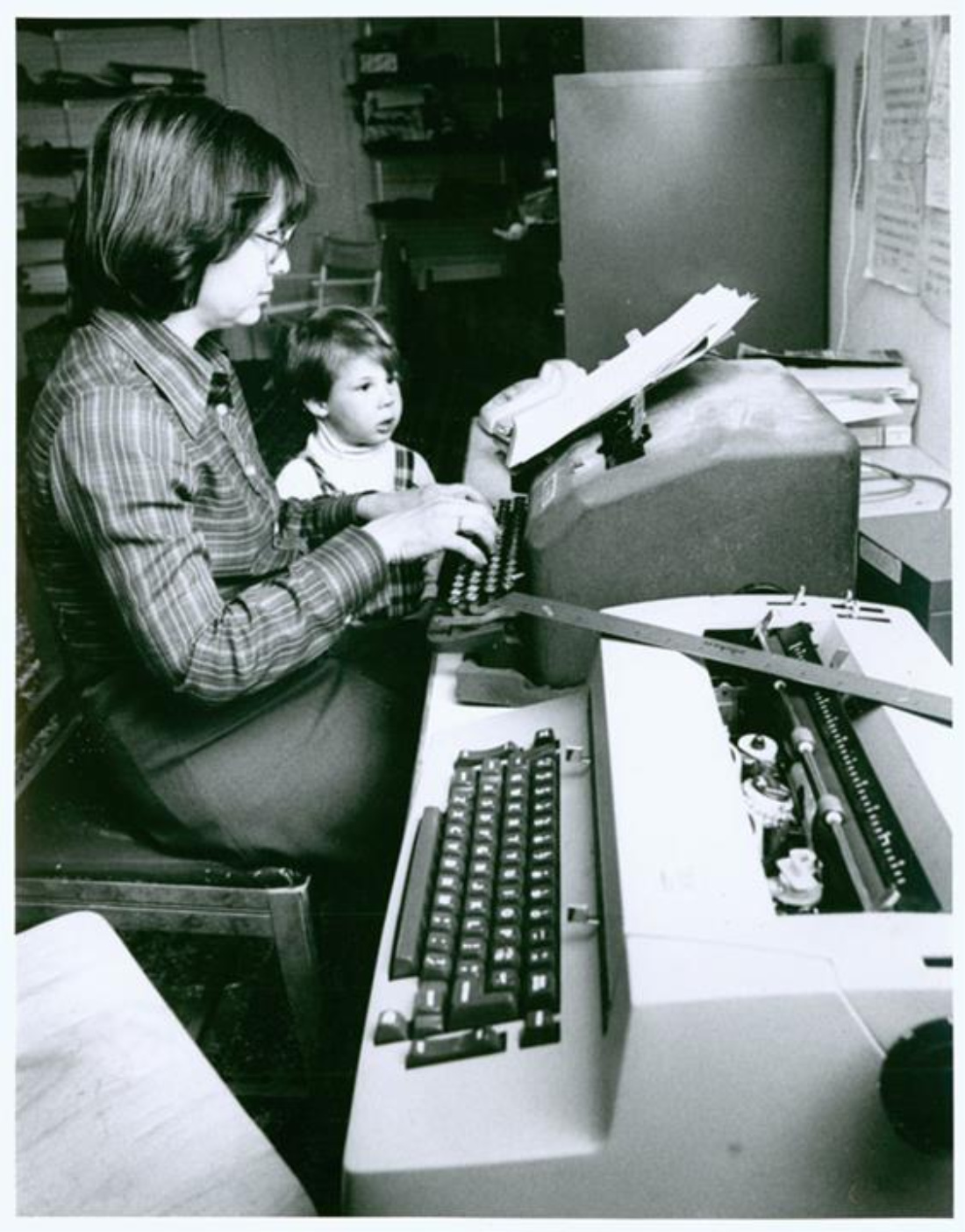

Interweave was founded in 1975 by Linda Ligon, a high school English teacher from Fort Collins, Colorado who had learned to make publications by mentoring the high school newspaper staff. After taking a weekend weaving class taught by a local woman in a converted chicken coop, she’d fallen in love with the craft. While on maternity leave when her son was born, and finding herself “not good at being a stay-at-home housewife and mother,”

Ligon decided to start a regional weaving magazine that would serve the western states. The timing was good. Handcrafts were gaining popularity nationally and Ligon found she was uniquely suited to writing about the people who made them.

Linda Ligon and her son David. Interweave got its start on Linda’s kitchen table while she was rearing her young children in the mid 1970s.

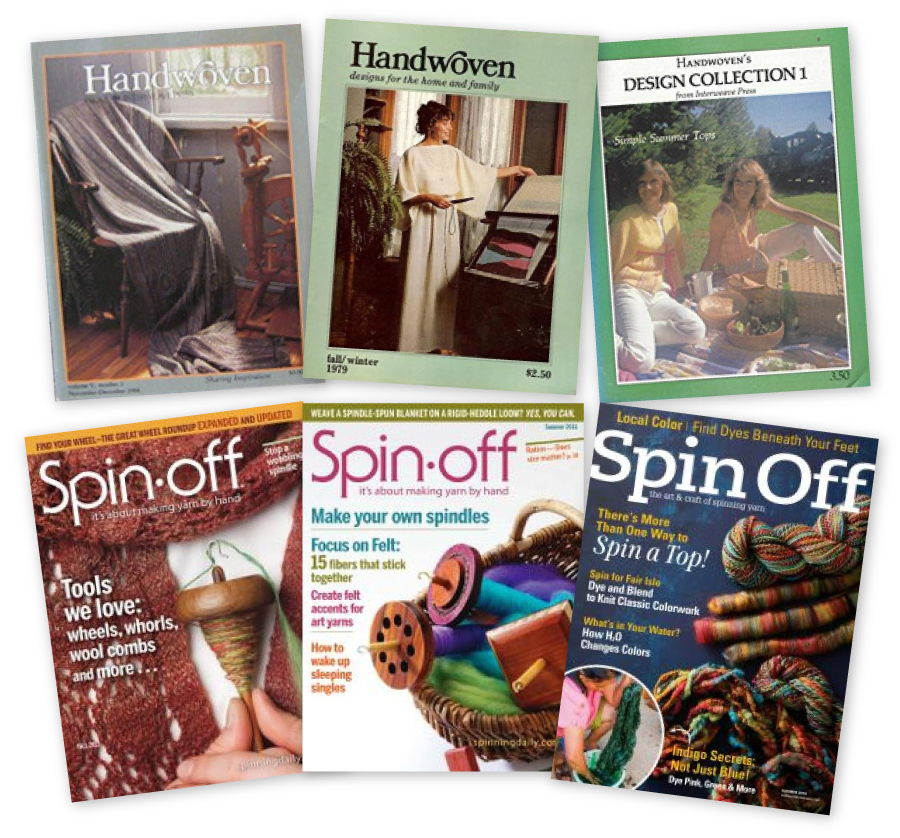

The company’s original magazine, Interweave, was soon subsumed by the more popular, Handwoven. Spin Off magazine came next, and then she began publishing books. When Ligon’s husband quit his job, Interweave became their main means of support.

Putting People First

Part of this was due to Ligon’s core value of putting people first. “Linda could really speak to the authors and they trusted her because they knew that she really cared about the community,” Moreno says. “At any meeting when we talked about new products — sure somebody had to run a spreadsheet in the end — but it was always about what people wanted and were interested in, how they learned, and how they could express themselves.”

Putting people first also meant investing in staff. Although compensation was often not high, opportunities were plentiful. “I do think Interweave was responsible for giving opportunity to a lot of people,” Ligon told me over the phone last week. “That was something that was really important to me. People came on staff in a fairly subsidiary role and just rose on up because they were smart and they cared.” After all, she herself and her early editorial team came to publishing as novices and had taught themselves by emulating the best books they could find in various enthusiast markets.

Alden Amos explains spinning tools to Linda Ligon.

A Deep Love of Craft

Ligon’s love of craft could also be seen in Interweave’s dedication to quality photography, editing, and technical accuracy. “We always felt that presenting our material, whether it was about how to make a thing or presenting an artist, we always wanted it to be true and beautiful,” she says.

Interweave publications were top-quality teaching tools. A lot of that had to do with the step-by-step photography taken by Joe Coca. According to Ligon, Coca’s work played an integral role in the company’s success. “If we were going to be showing these beautiful pieces of work, we wanted the presentation to live up to the real thing,” Ligon says. “He totally got that.”

Behind the scenes at an Interweave Crochet photo shoot.

Photo courtesy of Kim Werker.

The photo stylist attending to the details.

Photo courtesy of Kim Werker.

Weaver Liz Gipson, who began working at Spin Off magazine in 2000 and stayed on at Interweave in various editorial roles through 2009, put it this way: “Interweave was a literate effort at making craft presented.”

The company was dedicated to both preserving traditional crafts and to finding new audiences for them. Melanie Falick was editor for Interweave Knits from 1999 to 2003 where she says Ligon allowed her to bring human stories into the magazine; stories about the role that knitting played in people’s lives.

“Making has such a rich history that goes back to the beginning of time, yet there are so many people that just don’t respect makers,” Falick says. “Interweave was dedicated to making sure that this information wouldn’t be lost, or be boxed up in a museum. They brought it to the present and kept it alive. And they weren’t talking down to us. People loved Interweave because of that.”

The Dream Team

By the late 1990’s the company had so many product lines and divisions that Ligon felt ill-equipped to make all of the business decisions on her own. She assembled an all-female executive team (Marilyn Murphy, Linda Stark, Dee Lockwood, and Suzanne DeAtley), often referred to by employees during that period as “the dream team.” In 2000, at a time when only three Fortune 500 companies had female CEOs, a women-led publishing house was certainly an anomaly.

The “dream team.” Left to right: Linda Ligon, Linda Stark, Dee Lockwood (seated), Marilyn Murphy, Suzanne DeAtley.

Photo via the Cloth Roads blog.

One of those acquisitions was Quilting Arts, a magazine and book publisher founded by Pokey and John Bolton. They’d turned down other offers, but knew that Interweave would be a good home. “When I thought of Interweave I thought of integrity,” Pokey Bolton says. “I told them I couldn’t go down in page count or paper quality. Those were things our readers depended on. And they were respectful of that.” Pokey Bolton came on as Editorial Director for the Quilt and Paper Division, a role she held for five years and one that allowed her to grow the brand to include new magazines and book titles as well as a PBS television show.

In 2012 Aspire sold Interweave to F+W where, unfortunately, top level leadership didn’t seem to value crafts or the people who made them, and failed to understand the crafts consumer. While the staff who stayed on tried valiantly to continue to put out quality publications, Interweave’s brand reputation was tarnished with each passing year.

What’s Next?

Even so, Interweave continues to have meaning for crafter consumers and those in the industry. The decades of positive impact continue to reverberate throughout our making lives nearly every day. So many of the books and magazines we read, the relationships we’ve formed, and the opportunities we’ve been given, stem from this single company. And now we’re at this fragile moment.

Ligon hopes Interweave lands in the hands of a strategic buyer, someone interested in rebuilding the brand, and building a company that lasts. “That would be perfect, wouldn’t it?” she says. But she’s also a realist. “You know, if it goes away? Things do leave their mark and then they go away. That’s life,” she says. “We all die.”

Still, as she told Mitchell, she’s proud of the quality and the stature that Interweave products have had in the publishing and the craft community. “It’s the making of stuff and it’s the working with people to do it. It’s been very, very satisfying.”

What a lovely article during this trying time in the industry. I hope somehow this all ends with a positive outcome for those who have put so much of their passion and integrity into Interweave and their publications.

Thank you so much for writing this. THIS is a story that needs to be told, and that folks need to know about Interweave. Things have to change, and sometimes it is heart-wrenching to watch the change unfold. But the legacy of Interweave is far-reaching, and one that has blessed me so many times.

The heart of Interweave – the people who work there – is still solidly in place. When we moved our yarn/quilt shop next door to them last summer, they strung a welcome banner up in the tree outside of our door, made a poster full of individual welcome notes, and about 30 of them were lined up along the sidewalk the first morning we re-opened in our new location. They are fully supportive of the industry and the people in the industry. They love what they do and have a passion for sharing it with others. The new buyer of this brand will be lucky to get them, and we in the industry will be lucky to keep them!

So glad you published this story, Abby. Such a shame to watch the F&W bankruptcy and the broad impact that will have on the craft industry. It is inspiring to read about how Linda Ligon followed her passion and built Interweave. Love seeing the Dream Team!!

Truly hope a caring and insightful long term investor will see the opportunity and buy Interweave.

So sorry to hear that we may lose interweave. I have learned so much from their magazines and patterns. Hopefully someone will buy them and continue Linda’s legacy.

As a fledgling knitwear designer, my first cover was Interweave Knits, Summer 1998. And my second, Fall 1998.

These brought me to the attention of Editor Melanie Falick who later tapped me to write my book, Knitting Lingerie Style.

It’s difficult to hear of the publications hat meant so much to my early career, struggling and (in the case of Knitter’s) dying. I echo the sentiments that hopefully someone with deep pockets and a commitment to the industry will step in and save Interweave.

I can trace my weaving life back to the beginning of this great magazine what an inspiration thank you

My favorite crochet magazine. I am going to miss the physical magazine. May a buyer be found and it rises again to be athe best yarn magazines again

Thank you for this story. Learning about the people and passion behind Interweave makes me see the brand in a whole new way. It IS very special.

Interweave was so important to spinners and weavers and to our business, Straw Into Gold that began in 1971, just a few years before Linda began Interweave. Alden Amos and I did some small books and were so pleased when Interweave republished and gave Alden the chance to do his big book! Bette Hochberg was an early author of spinning articles which were appreciated for her detailed insights. I taught at some of the Interweave events and everyone was so inspiring. I hope someone is able to take the chance to buy it and keep it going!

Thank you, Abby, for writing this very important story. I would not be the person I am today – stronger, hopeful, better self-esteem, a maker, a helper and grounded in simplicity rather than consumption if it were not for Interweave and all of the people through the years who had a part in everything they did. I’m not an author or featured artist – I am a longtime subscriber to many of the magazines and a voracious reader of Interweave’s books. In 2001 I was in a horrible car accident and the driver who caused it was never found. I am so very grateful to be alive. Several times the doctors did not expect me to live. After a very long hospitalization and years-long recovery, I am a textile artist and I’ve pretty much stayed under the radar on purpose because I still have three more reconstructive surgeries to go through. In 2005 when I was finally able to sit up for extended periods of time and I was making progress with walking I decided that I had to find a new purpose in life because there was no way I would be able to return to my profession. I had been a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Cardiology and Cardiovascular Surgery. I had always loved the needle arts but I was still in the healing process with my arms and hands from orthopedic crush injuries. In 2005 when I was able to sit at my computer and I could move the mouse around I found Interweave and the wealth of magazines, books and the website. I totally immersed myself in learning more about weaving, crochet, knitting, embroidery and quilting. Then came Cloth Paper Scissors and I loved that, too. As I progressed in my recovery I kind of settled into art quilting and mixed media art. After several more surgeries I was able to put a needle in my hand and use these in hand therapy. I experienced so much more than learning about the arts. I found a community of people who loved to share and support each other. The encouragement and acceptance I received and the motivation to stick with it and to think creatively every day was invaluable in my recovery and it continues to be. I am eternally grateful to everyone who have been a part of Interweave and it is surely my prayer that the right buyer will connect with the company so it can continue. Thank you again, Interweave!

Dear Becky,

What an incredibly awful story! And, an equally incredible wonderful healing experience. I’ve been weaving regularly for over 35 years, and even though I have no tragic story like yours,I can’t tell you how much I have grown through Handwoven magazine and all the friendships I’ve acquired through guilds, workshops, books, conventions, etc. Being an artist requires many people and resources to make you who you are. It breaks my heart to see what’s presently happening with those resources: cancelled conventions, classes, zoom guild meetings and now we may not even have our magazine subscription to look forward to. I pray a worthy company comes along to help continue the passion that we all have. And “Thank you” to Linda and all the amazing people who have worked diligently to make Handwoven such a beacon to so many of us.

Sincerely,

Leslie Kirschenbaum Alperin

Take a look here. Linda has kept Handwoven going: https://longthreadmedia.com/

A lovely tribute to a company that was an inspiration to all of us who publish craft books. Linda and the Interweave staff have been great colleagues for Storey, and many former Interweave staff members are among our most knowledgeable and admired authors. So many timeless Interweave books continue to be go-to resources.

I started my relationship with Interweave Press with Threads magazine and continued with Spin Off and Piecework. However, SOAR, Spin Off Autumn Retreat, was what had the greatest impact on my growth in the fiber arts. There isn’t much support out there for serious spinners but SOAR was just that. I as so excited to meet Linda Ligon and Marilyn Murphy and attend in-depth three day classes from some of the best spinners in the world. As I progressed from serious spinner to spinning instructor it was just what I needed to deepen my knowledge and be with others like me. What a loss then F+W decided that SOAR wasn’t growing and would not continue. They didn’t understand that the size was perfect and that those who attended brought others into the craft and to F+W’s products. They didn’t understand us or the craft community. Hopefully someone who does will purchase this wonderful company that has meant so much to so many of us. We are fortunate that Linda built the Interweave and a community around it. She is wonderful and so are all the women who worked there throughout the years.

Excellent retrospective. I started as a weaver and have the Handwoven and Spin-off magazine covers featured. Like Linda, my hope is that there is a buyer out there to follow the quality inspired by her and Interweave publications. My current quilting passion has been enhanced by the current publications related to the art and craft industry. Such a shame that publishing is suffering in this on-line culture.

Thank you so much for this, Abby – it makes me feel surprisingly emotional. I was working in the editorial department (on the magazine side) at Interweave when your book came out, and I remember those days well. Linda Ligon is one of the most inspirational people I’ve ever known, and my time at Interweave was an incredibly formative experience. I really hope the company lands somewhere with people who value the craft, and the process of teaching and learning.

Wonderful article, Abby. Fascinating look at the history and impact of Interweave. What a pioneer!!! I hope the F+W publications find a home — the magazines will be sorely missed. I was very fortunate to work with wonderful editors at Cloth Paper Scissors, which I miss terribly, and the short-lived but beautifully done Artists & Makers. I loved writing for both and meeting the artists who filled those pages. Thanks for the history lesson.

I subscribed to HandWoven from almost the beginning! It was a lifeline and inspired me during my first years as a spinner and weaver over 40 years ago. We were dairy farmers with 4 young children living in the boonies of Central NY and I couldn’t wait for my HandWoven to arrive each month! Linda Ligon was so relatable… she worked on projects while sitting on bleachers while watching her son play Little League baseball just like I did! I hope a way can be found for the treasure Linda created to continue!

A wonderful article about an important resource to all who work in fiber. Have many Interweave publications on my bookshelves. Always a class act, full of well-researched information and gorgeous photography.

I remember when I first discovered Handwoven in the early 80’s. I didn’t know there was this whole weaving community out there. ! I grew up weaving with my grandparents and two great aunts. They would have loved Handwoven and to have all that wonderful information, sharing and help. Thank you Handwoven! I pray that things will work out.

I have fo.lowed and subscribed to Handwoven a d Soin Off from the beginning and also bought many books and e courses. I woul be deeply saddened if this rich resource ended

What a wonderful tribute and history Abby. Like you, Interweave —Spin Off in particular, but also Handwoven and Interweave Knits—changed my life in more ways than I can count. From the first magazine I held in my hands in the 1980s “Oh my goodness, other people take this as seriously as I do,” I was smitten. Then came articles, projects, issues featuring my work on the cover, classes to teach at SOAR, an introduction to my future editor Melanie Falick — oh it goes on— all of which have led to connections with spinners, weavers and knitters around the world, which means that Linda’s work has, directly or indirectly, guided my entire adult life. I can never thank her enough. Her work continues to reverberate through the textile community. May it continue in a form that does service to all that she started, and all the amazing and passionate individuals who keep the work alive.

When I started Wild Fibers Magazine in 2004, I looked to Linda Ligon as the publishing icon of the fiber industry. My respect for what she created over the previous decades of dedication and inspiration has only grown since I have navigated my own path. As a print-only magazine publisher, I understand the challenges of remaining in the black as technology supplants the irreplaceable qualities of print. I cannot imagine, however, not only the financial hardships to countless unpaid designers and contributors that the demise of F&W will mean, but the loss to the industry as a whole. Yes, there are a few other fiber-related publications still in print, including PLY and Fiber Arts, and my own Wild Fibers, but there is only one Interweave brand and as Linda Ligon says, if it does not rise from the ashes no one will question that it has left its mark

What a lovely article. Writing and designing for PieceWork has changed my life — I have learned so much and met such interesting and inspiring people. I so hope that a purchaser will step in to continue the Interweave family of magazines.

A wonderful article on the historical and modern impact of people working with fiber. Hope all works out for this wonderful resource and continues for many, many years to come.

Interweave made my knitting and spinning world a better place, and I am very grateful for all the work so many put into its success.

Piecework gave me a bit of family history I would never have stumbled across on my own: an article there once told the tale of a woman who ran for lieutenant governor of the then-territory of Utah. (Utah was later forced to give up women’s suffrage in order to be allowed to join the Union as a state.) I don’t remember the woman’s name, just her outrage that a man she described as a grumpy old guy had told her she couldn’t use the local church building for a political gathering. (Separation of church and state and all that.)

I stared at that Swedish immigrant’s name. There could only have been one of those. The town was right, too. That was my great-great-great grandfather!

I think Interweave was created just as people like me became interested in fiber, sheep, weaving and spinning. It was THE ONLY PLACE for us to find others and contribute to the reemergence of interest in fiber arts.

City folks perhaps had guilds but for many of us, Interweave magazines were our guilds. And many many of us found our way into the magazine, too.

I was a new designer, inventor in 1999 and my products were given a positive write-up in Interweave Magazine. I was thrilled and excited to have such a wonderful review by a noted magazine. We are still plodding along but at a much slower pace and I am so sorry that this downfall has occurred.

I’ve been enjoying Handwoven ever since I began weaving in 1980. I even purchased all the back issues that began before that so I now proudly own the entire collection. I look forward to every new addition. Even though I’ve had wonderful instructors, attended multiple conferences and have many friends among the two guilds where I’ve always belonged, Handwoven magazine has always been a staple in my weaving world. I can’t imagine being without it. It’s a constant reference for me, both for content and for exploring new ideas. I’ve met Linda Ligion on several occasions and have always been amazed and appreciative of her insite and dedication to textile artists. I am so sad to learn what’s been going on behind the scenes. I truly hope the company is purchased by people who have a strong compassion for textile artists. The weaving, spinning, quilting, basketry, etc. world definitely needs this to continue. And thank you to all of those wonderful people who have worked so hard to make Interweave Press the amazing company that it’s been.

With the exception of one or two of the first magazines, I have them all and still go back to them time and again. I have been weaving since the early 70’s and even have a picture of my Fellowship Cloak in one issue. One thing I have noticed about myself as I get older (I am now 76) I hate change. Change is not always for the good of humankind. What on earth will we do if there is no Interweave Press?

My mother was a charter subscriber to Handwoven. Since her passing, I have filled in missing issues and have continued to subscribe to this date. It still is a major reference source for me, even with the advent of on-line information available. I am saddened to think that Interweave Press will “fade into the sunset”.

As a former member of the Spin Off editorial staff and SOAR organizer, this article makes me very nostalgic. Thanks for the telling the story, Amy!

Yikes! I mean Abby!

I will never forget standing in my dining room, somewhere around 2000, talking on the phone with IK editor Melanie Falick as my first publication was being edited, before it came out in IK. I kept pinching myself. I could not believe it! Melanie was famous to me!!

My first articles and designs in IK and Spin-Off were absolutely key to my development as a freelancer- as a writer, teacher and designer. I look through all these comments and feel like I am revisiting my email inbox from so long ago. Thank you, Linda Ligon and Interweave! The connections and friends I have made through the fiber arts world are lifelong ones…and yes, it started for me when I got my first copies of Spin-Off. I was the only teenager I knew who liked to spin, weave, dye and knit. All those articles enabled me to succeed. I will always be grateful for Linda Ligon’s vision, even though I have never met her. Thank you for this article.

This is the best article I’ve found in the start up and history, right through to present day, of Interweave. I have lived in the Denver area since 1999. I discovered knitting and crochet in the early 2000’s and in doing so discovered Interweave publishing. I took myself and my best friend on a field trip to their offices in Loveland one day. I loved everything that Interweave stood for: Crafters and makers hearts and souls.

I see that the company that ended up buying Interweave, F&W Media, had one goal in mind……$$$$$$$$. It makes me feel bad for all the employees that still care about substance over dollars and for all past employees and leaders to see this happening.

I still love Interweave. Just not F&W Media.

I would like to have an update from some who knows if a buyer was found for Interweave. I came by this article buy searching for the reason why a certain craft book was not reprinted: Angora: a handbook for spinners by Erica Lynne. This book is going for crazy prices on book dealers web sites. What is the Author up to now, can’t find any information on her? Let us preserve this knowledge we can’t let such knowledge slip though the cracks of time!

Hi Bryan, Interweave was bought by Golden Peak Media: https://goldenpeakmedia.com/communities/crafts

I can’t seem to access the golden peak site. Or rather I can’t find my video downloads or any of the other purchases. What is going on?

Hi Jane,

You should be able to get there from here: https://goldenpeakmedia.com/communities/crafts

Thank you for writing this tribute. Like so many others, I owe a lot of my career as a weaver, teacher, writer and artist to Linda and Interweave Press. We have grown together and Interweave has given me much inspiration over the years as well as invited me to share my knowledge. It is impossible to state how much Interweave has changed and bettered so many of our lives. I know I would not be the woman I am today without the help of Interweave.

That’s lovely to hear, Karen. Thank you for your comment.