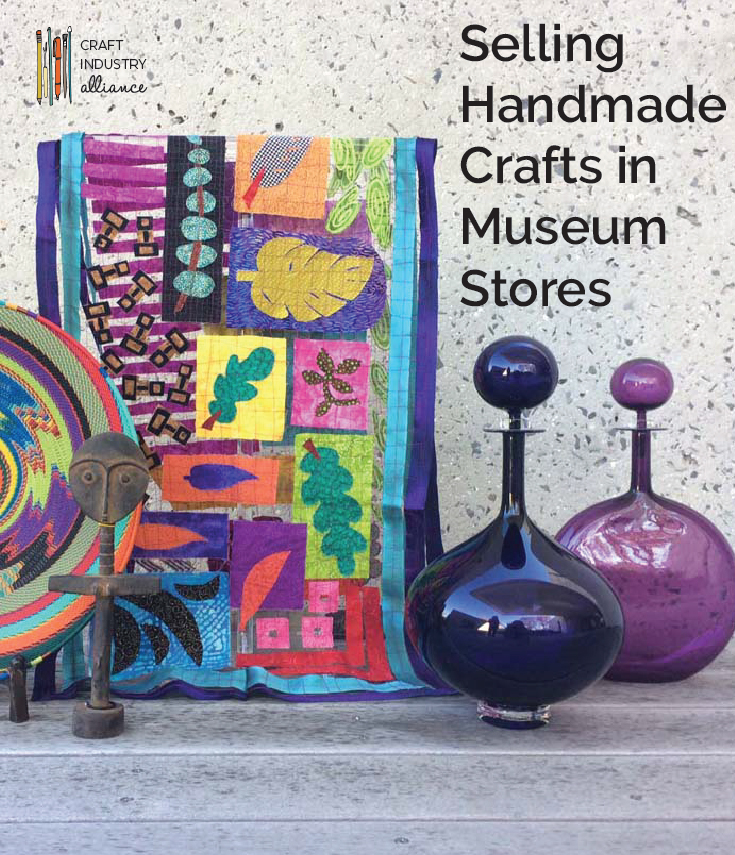

An Ode to Matisse scarf by Joan Edelstein among other artisan items available at The Barnes Foundation’s museum shops in Philadelphia.

Photo courtesy of the Barnes Foundation.

Friends started buying Edelstein’s scarves right off her neck, so the Austin-based artist created a side business featuring her Ode to Matisse flight of scarves. Julie Steiner is director of retail operations for The Barnes Foundation’s museum and gardens in Philadelphia. The Barnes has a huge collection of Matisse, and Steiner is always on the lookout for Matisse-inspired items to carry in the shops. She stopped by one of Edelstein’s shows and it was love at first sight; Steiner loved the scarves and the two women hit it off.

The Barnes is now a cornerstone wholesale customer for Edelstein, whose work is carried nationally in high-end gift and museum stores. “The nice thing about having my work in a museum store is that I know people will appreciate it,” she says. That and the fact that museum stores can offer a rare opportunity for artisans to collaborate on custom projects, can become a channel for steady sales, and can bestow the aura of a curatorial blessing.

Museum stores have a different set of criteria than standalone shops. Merchandise must be tied to the museum’s exhibits and reflect the museum’s overall aesthetic. Given that art and craft can represent facets of nearly any topic, from archeology to zoology, the mission provides a helpful filter for artisans hoping to build long-term relationships with shops.

Edelstein was ready to be discovered. Even as she experimented with the creative process, she was researching related aesthetics. When she realized that her process was similar to that of Matisse, she cultivated that approach and summarized her creative journey on tags attached to the Ode to Matisse scarves.

All of this told Steiner in a glance that Edelstein’s work would resonate with Barnes visitors. When Steiner subsequently learned that some customers hung Edelstein’s scarves on their walls, she commissioned larger pieces intended for display only.

Found wood sculptures by Jason Van Duyn, a Raleigh, NC woodworker. The pieces are sold at the Mint Museum store in Charlotte, N.C.

Photo courtesy of Jason Van Duyn

Points of View

Special exhibits offer artisans a chance to design a special collection and to start a museum store relationship, says Stuart Hata, director of retail operations for the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and president of the Museum Store Association. “We want to come up with something that burnishes the craft artisan’s reputation and that is authentic to the exhibition and the artist,” says Hata.

A few years ago, the museum brought in a temporary exhibition of the Quilts of Gee’s Bend. It collaborated well in advance with local quilters to create kits and even commissioned a wood crafter to design and produce a limited run of archival wood boxes. To accompany a different temporary show of Hawaiian featherwork, the store commissioned a printmaker to design a line of block-printed towels and brought in an array of contemporary Hawaiian feather crafts.

Copyright and permissions, though, rein in creative opportunities pivoting on work not in the public domain. The rights to many works are controlled by family trusts or other legal entities, explains Hata, and often these entities put strict conditions on exactly what and how images of the work may be used for merchandise. For example, a print might have to be of a minimum size, and sold only in a certain type of frame with a white mat.

“People ask, ‘Why don’t you make Georgia O’Keefe tote bags?’” he says. “We can’t.“

These restrictions are a wide-open opportunity for artisans like Edelstein who can evoke the spirit and aesthetic of an artist or work without infringing on rights. Managers are very open, say Hata and Steiner, to custom designs produced in limited quantities specifically for events or special exhibitions. Such contracts offer a lucrative contract for artisans while furnishing the shop with a genuinely unique offering.

Ceramic artist Nicole Aquillano has developed a specialty of custom-designed collections that translate architecture and landmarks to tableware. Each collection provides the sponsoring shop with a unique offering, and provides Aquillano with a steady production and cash flow. After an initial consultation with a potential client, she produces prototypes, for a fee, so that the designs can be fine-tuned before production. Her work is carried by the Barnes and other museum shops.

Show and Be Shown

Museum store buyers constantly scout new artisans whose work complements their museums’ missions. Exhibiting at the right wholesale shows and at high-end consumer shows is one of the best ways to meet museum shop buyers.

“If someone’s at a juried craft show, it signals a certain level of consistency and reliability,” says Steiner. “It doesn’t help me to get one delivery but not another.”

Here’s how and where to get discovered.

- American Craft Retailers Expo, annually at the beginning of the year, is usually held in Philadelphia.

- The American Made Show is held in January; the show is sponsored by the publishers of Niche magazine and is one of the major wholesale craft and artisan shows.

- The Smithsonian Craft Show is a longstanding tradition in Washington, D.C. This high-end public show is usually held in April.

- The Renegade Craft Fair is the largest independent craft fair in the world. From its Chicago office and roots, this offbeat public show has expanded to eleven more markets. The shows focus on the quirky, recycled, and alternative.

Once you are discovered, make it easy for the buyer to find you in her files.

- Print an oversized postcard with images that illustrate the scope of your work and with key contact information and price points. Buyers keep files of artists’ contact information for planning.

- Be sure your website is current and easily found online. Have you optimized the site for your own name, your region, and the type of work you do? Make it easy for shop buyers to find you even if they misplace your contact information.

- Don’t count on photos and your website to make the case. Stores are selling actual goods and buyers must see your work in real life to commit.

An Appalachian themed display at the museum store of the Mint Museum in Charlotte, NC.

Photo courtesy of the Mint Museum

Local Showcase

Janet Micek, visual coordinator for the shops at the Charlotte, North Carolina, Mint Museum, views the museum’s stores as a liaison between the state’s artisans and the art-loving public. She seeks out indigenous crafts and items that reflect the state’s history, natural resources, and current creative culture. She also carries a spectrum of imported goods that represent the Mint’s core collections of international arts and crafts.

That’s why the Mint carries Jason Van Duyn’s “found wood” sculptures. The eroded bowls and vases are extracted from weathered Carolina wood. Van Duyn says he makes sure that the retail prices he charges at his website are consistent with prices for his work at the Mint and other shops. “They don’t want to go onto your website and see that they’re being undercut,” he says.

And even though museum store shoppers expect to find higher-end goods, it’s still incumbent on artists to “help these retailers out by providing information about what you make and why you make what you do,” he says.

Practical Magic

Museum store buyers juggle a wide variety of practical considerations for their mix of merchandise. Here are some tips for artists and artisans hoping to break into this type of retail location:

- Visitors often are from out of town, seeing many venues and shopping at each. Buyers want to offer them goods that are easily packed and unlikely to trip up airport security procedures.

- As visitors have just spent money on admission and possibly refreshments, buyers want to stock their inventory with unique souvenirs at every price point, starting with small magnets that reproduce images iconic to the institution.

- Before approaching a museum store buyer, practice and streamline your story about your creative philosophy, work, and following. Be prepared to show how your work has sold at shows and shops that likely have similar followings to the museum store.

- Always visit the shop in person before asking for an appointment to introduce your goods to the manager. (And always set up an appointment.)

- Ask about the store’s schedule of trunk shows—a time-honored, low-risk way to see if your work is a fit for the shop.

- When you introduce yourself and your work, include tags and shelf talkers that explain your point of view and story in a sentence or two. Help the buyer see how your work will engage browsers.

- Create versions of tags that link your work to the museum’s collections and mission.

- Provide short biographical and creative profile stories that the shop might use to showcase your work at its website.

And know that museum shop buyers want to surprise shoppers just as much as they want to be a reliable source for beautiful, thoughtful, quality items.

“The weirdest little thing we sell, by the dozens, is a ceramic egg separator with a face on it, for $15,” says Micek. “They’re made in Asheville. The artist also makes beautiful bowls and mugs that we carry, but that egg separator is just a silly thing and people go crazy for it.”

Joanne Cleaver

contributor

Joanne has been writing about entrepreneurship for 30 years and quilting for 40 years.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks