However, there is a small but determined portion of the magazine marketplace making itself known: the self-publishing arm. With niche content, this segment focuses on providing subject matter that suits a small but loyal following. Content is no longer limited to a traditional publishing environment, and this development has opened up the marketplace to people who have knowledge to create great content but would not have had access to the tools required to produce a magazine. These are often self- or seed-funded and have one person on the masthead: the owner.

Is the focus on niche content the secret weapon to creating a successful magazine in challenging publishing times?

The elder stateswoman of indie magazine production is Janine Vangool, founder and creator of Uppercase Magazine. Vangool feels that small businesses can publish at a more manageable scale than can larger publishers. “Uppercase has always been a very niche magazine. At eight years and counting, the magazine hovers around 5,400 subscribers now. That’s a healthy readership for my business. And though it certainly looks like a lot if you’re just launching a new indie magazine, if you’re publishing a mainstream magazine with a big publisher that’s small potatoes! But I’m happy with this slow and steady growth. I like it small like this. I realize it limits the potential reach of the magazine, but this is what works for me.”

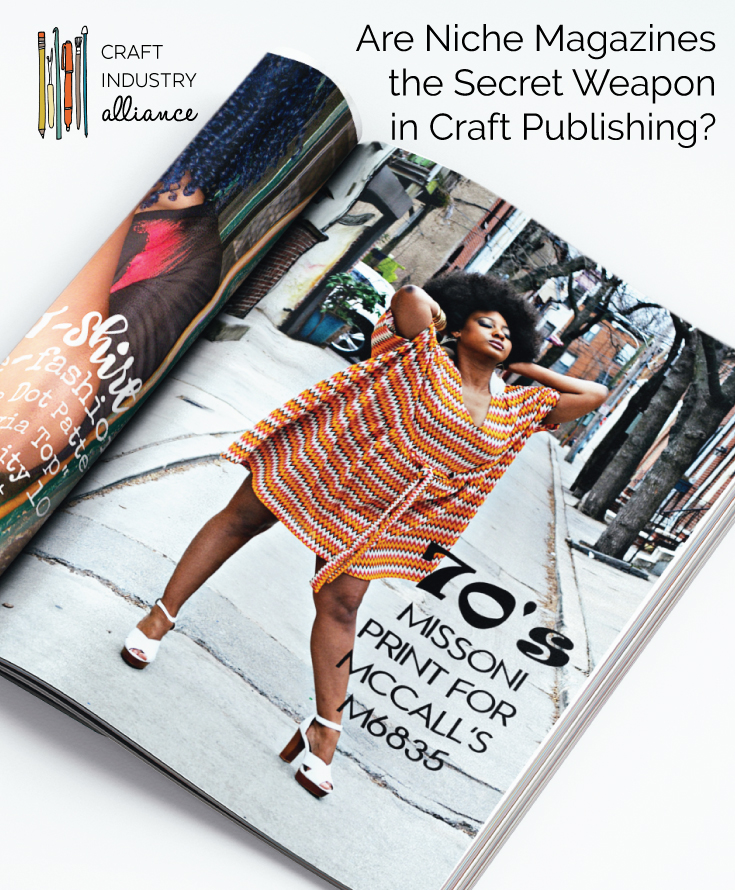

Sometimes in the case of niche publications, inspiration comes in the form of creating a magazine the owner would want to read herself. Michelle Morris, who is in the process of creating Sewn Magazine, decided to start her niche project after a fruitless search for a magazine that featured women of color who sew.

“I decided to create Sewn because in my search to locate a sewing magazine that showcased African-American makers, I found nothing! Heck, I could not find one magazine with even one African-American contributor or feature story. I was dumbfounded because I know we are out there.”

She hopes that by creating a magazine for a portion of the market that she knows is untested, her niche-focused content will be what makes her stand out from other sewing and dressmaking magazines.

Digital versions of magazines can help keep printing costs down but offer a richer product for readers. When Julie Bonnar created The Pattern Pages, the first independent digital magazine for dressmakers, she decided that her journalist know-how in creating print craft magazines could also stretch to creating a digital experience:

“Five years ago, I left work as an editor of one of the major sewing magazines. I became disillusioned as at the time none of the magazines were concentrating on dressmaking and definitely none were aligning it with fashion. As a craft journalist, I still work on print magazines, as I believe these are still very important to the industry too,” Bonnar said. “For The Pattern Pages, we decided the digital route was best for us, and our users. We wanted to create an interactive magazine that could be read as well on a computer, laptop, tablet, or mobile and would link directly to all the companies mentioned within.”

“As a small business, we wanted to be able to deliver a quality professional magazine that could rival any of the print magazines,” Bonnar said.

“If I reach the fundraising goal, that will secure the magazine for two full issues, which would give me a big head start and not tie up monies that could be used for the things I’ve put on the back burner,” Morris said.

Vangool didn’t have the option to seek financial help on a public platform when she started Uppercase in 2009. Kickstarter launched the same month that Uppercase did, and she used $55,000 of her own money to foot her print bill. However, she argues that using her own money made sure that she succeeded: “Supporters might believe that a successful Kickstarter equates to a successful project launch. In the case of a magazine, that is only proven over time as more issues are released…. In retrospect, I’m glad that I decided to self-fund the launch of my magazine. I think it demonstrated my personal commitment to making Uppercase Magazine a publication that could reliably publish high-quality content on a regular schedule. I was committed to making Uppercase my main business and my creative focus right from the beginning.”

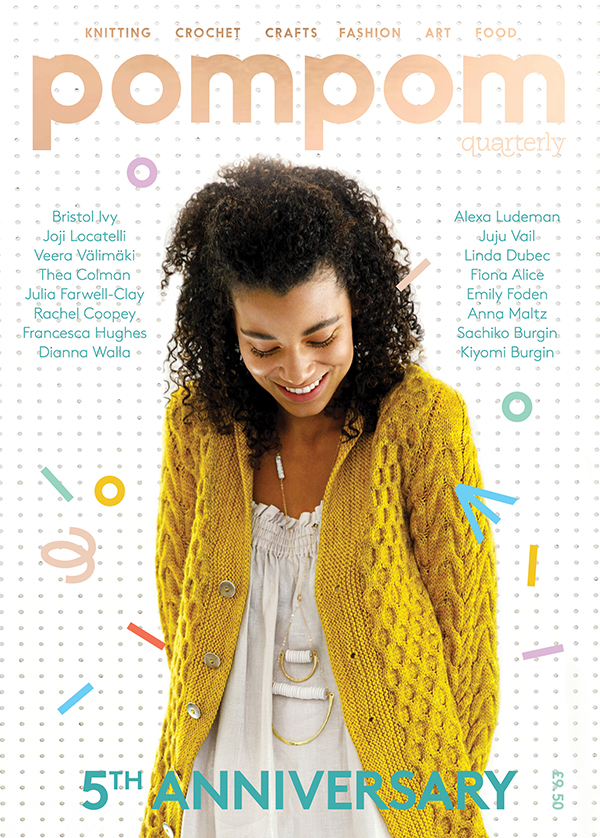

Bonnar has also decided to forego raising money and has funded The Pattern Pages herself, which she knows is a bit of risk but one that she is prepared to take. Fernandes and Gluck also decided to fund their magazine themselves, with the understanding that growth would take more time: “We did almost 100% of the writing and knitting pattern design ourselves, so really our biggest upfront cost was printing. We very much took baby steps at the beginning and grew organically from there. I suppose having subscribers is not unlike having backers from Kickstarter, but at the same time I think there was less pressure than a business might feel from going the Kickstarter route.”

With the ability to create a magazine — in either paper or digital formats — easier than ever before and with alternative funding sources more readily available, is creating a magazine for everyone? Fernandes says, “Definitely try to fill a gap. Produce something that isn’t out there yet, fill that lack that you see in the market. There are a lot of indie magazines out there now — make sure yours is different!”

And perhaps the soundest advice comes from Vangool:

” ‘How do I launch a magazine?’ is a question that I get a lot and my advice is to do your research: understand your audience, get your print and other production costs figured out, and know your tolerance for risk.”

Maeri Howard

CIA special contributor

Great article, and timely, like most of your content ; ) — I just published my 6th issue of FABRIGASM, the Magazine for Lovers of African Textiles. The niche is a natural progression of my business, Cultured Expressions, an outlet for specialty fabrics, kits and related merchandise, as well as my workshops, lectures, special events and SewJourns(TM). I do a limited print run for each issue, then I make a digital version available for purchase after print copies sell out. So far it’s been published as a pet-project, “when i have time”, but because I’m now looking to expand it with advertising and sponsorships, I’m committing to more of a schedule. The Fall issue will come out in Aug/Sept, as September is African Fabric Month.

Great article, Maeri Howard! I love magazines. I love digital magazines even more than print these days as my crafty clutter is at an all time high. And I love that digital magazines have links.